At least according to LiveScience:

At least according to LiveScience:

The translation of the Bible into English marked the birth of religious fundamentalism in medieval times, as well as the persecution that often comes with radical adherence in any era, according to a new book.

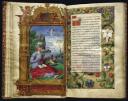

The 16th-century English Reformation, the historic period during which the Scriptures first became widely available in a common tongue, is often hailed by scholars as a moment of liberation for the general public, as it no longer needed to rely solely on the clergy to interpret the verses.

But being able to read the sometimes frightening set of moral codes spelled out in the Bible scared many literate Englishmen into following it to the letter, said James Simpson, a professor of English at Harvard University.

“Reading became a tightrope of terror across an abyss of predestination,” said Simpson, author of “Burning to Read: English Fundamentalism and its Reformation Opponents” (Harvard University Press, 2007).

“It was destructive for [Protestants], because it did not invite freedom but rather fear of misinterpretation and damnation,” Simpson said.

It was Protestant reformer William Tyndale who first translated the Bible into colloquial English in 1525, when the movement away from Catholicism began to sweep through England during the reign of Henry VIII. The first printings of Tyndale’s Bible were considered heretical before England’s official break from the Roman Church, yet still became very popular among commoners interested in the new Protestant faith, Simpson said.

“Very few people could actually read,” said Simpson, who has seen estimates as low as 2 percent, “but the Bible of William Tyndale sold very well—as many as 30,000 copies before 1539 in the plausible estimate of a modern scholar; that’s remarkable, since all were bought illegally.”

When Catholicism slowly became the minority in the 1540s and 50s, many who hadn’t yet accepted Protestantism were berated for not reading the Bible in the same way, Simpson said.

“Scholarly consensus over the last decade or so is that most people did not convert to [Protestantism]. They had it forced upon them,” Simpson told LiveScience.

Persecution and paranoia became the norm, Simpson said, as the new Protestants feared damnation if they didn’t interpret the book properly. Prologues in Tyndale’s Bible warned readers what lay ahead if they did not follow the verses strictly.

“If you fail to read it properly, then you begin your just damnation. If you are unresponsive … God will scourge you, and everything will fail you until you are at utter defiance with your flesh,” the passage reads.

Without the clergy guiding them, and with religion still a very important factor in the average person’s life, their fate rested in their own hands, Simpson said.

The rise of fundamentalist interpretations during the English Reformation can be used to understand the global political situation today and the growth of Islamic extremism, Simpson said as an example.

“Very definitely, we see the same phenomenon: newly literate people claiming that the sacred text speaks for itself, and legitimates violence and repression,” Simpson said, “and the same is also true of Christian fundamentalists.”

- Original Story: Historian: First English Bible Fueled First Fundamentalists

I guess the Bible didn’t exist in the vernacular, ever, anywhere, until Reformation England?

Vaguely interesting article replete with modern speculations and a potpourri of mixed historical references, but I don’t think it leads anywhere. (But what do I know? I’m not called an Am ha-Aretz for nothing.)

I’m not a newly literate person either, but I DO think the sacred text (the Bible) speaks for itself, without at the same time believing that it legitimates violence and repression.

I suppose that as the ancient Hellenistic world gradually drifted away from the lingua franca of Koiné Greek, the original Greek became less and less understandable, altho at first it WAS in the vernacular. I’ve read that until recently (maybe a century ago) there were still rustic peasants in Greece whose vernacular was still very close to the Koiné, so much so that they could understand the readings in church without a problem. (Modern Greek speakers, on the other hand, have almost as hard a time understanding the Greek readings and prayers in the Orthodox liturgy as the non-Greeks do. The language has drifted so much, and fewer and fewer Greek speakers are diglossic, knowing both katharévousa and dhimotiká.)

It seems to me, then, that the original Greek New Testament (and Septuagint for that matter) were the first vernacular bibles (oh, I guess the Latin translations were too, at first anyway), and because Greek stayed intact much longer and did not morph into a language group like Latin becoming the Romance languages, some people didn’t have to wait till the Reformation to hear the Word in their own tongue. In the Orthodox and not-so-Orthodox East, we have the Gothic bible translation of bishop Ulfilas, and the Slavonic translation of Kyril and Methodios’ school. So really, the vernacular bible was not completely snuffed out till Reformation times, but we tend not to notice what was happening east of the divide between Roman and Greek Christian worlds.

“The translation of the Bible into English marked the birth of religious fundamentalism in medieval times.” I guess this means that the Crusades and the Inquisition had nothing to do with fundamentalism.