What brings renewal to the church? There is no doubt that we are experiencing decline in the church and have been since the end of the 1960s. The membership of the Episcopal Church is supposedly over 2 million, but the people that actually show up on a given Sunday is under 800,000. Contrast that with the Diocese of Nigeria, which has almost 20 million worshipers on any given Sunday. I do not want to dwell on the troubles of the church. What we need to do, in part, is to look back on the life of Jesus and how early Christians also looked back on the life of Jesus to renew the church of their time.

Why look back to any time period other than our own? We Americans have a short memory. We think church history is when father so and so was the rector of our parish.

In order to look forward, we must learn to look back. Christians of the past often emphasized a particular characteristic of Jesus and ran with it to make it their own and to apply it to their own age.

As simple as it sounds,if we learn to pray like the early Christians and if we have a mission to be a light shining in the darkness—there is no telling what we can do as a church.

Look at Mark 1:35-39 You can already see the twofold pattern early in Jesus ministry—pray in solitude—then preach the Kingdom and set people free.

The Church of the early centuries was a powerful church. It was a movement, not a bearacracy, it was an organism, not an organization. It was alive, full of the Spirit of God—partly because being a Christian was a life or death decision. The Roman Empire would at any time request Christians to offer a pinch of incense to the emperor, a sign of loyalty, but also of worship. When Christians refused, they were systematically eliminated. To be a Christian was serious business. Tertullian, a Christian from the 3rd century said, “We are regarded as persons to be hated by all men for the sake of the Name—just as it was written. And we are delivered up by our nearest of kin also—as it was written. We are brought before magistrates, examined, tortured, make confession of Christ, and are ruthlessly killed—as it was written.”

In the early fourth century, the Emperor became a Christian, making the times of persecution an unfortunate memory. Christianity became legal, and within a few generations it became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Not everything about Constantinian Christianity was or is bad. The doctrines of the faith were solidified. The canon of the New Testament was made official, church order was put in place, beautiful structures were built for worship.

But when you go from a faith that is a life or death decision to the faith of an Empire, then the cost of discipleship is cheapened, and the spiritual lives of Christians becomes lax. I do not want to be simplistic or Hollywood about this. Hollywood has a way of making medieval Christianity into one corruption after another. Christianity has always been a big movement that is both East and West, it is a worldwide phenomena, not a monolithic organization.

Still there were many who remembered the persecutions and the power of the church in those days and compared that with a church that did not require anything other than that you show up. One became a Christian during the persecution era after a catechumenate process of formation and self-denial that lasted three years. One became a Christian after persecution often simply by being born—the closest thing to self-denial being Lent and other penitential occasions. The three years of intense training were reserved for priests, the strict regimen of study and formation was reduced to the 40 days before Easter.

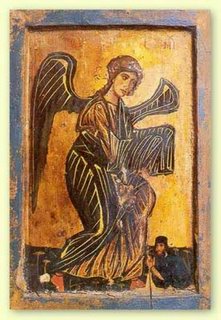

Faithful Christians looked at the opulence of some clergy and the lack of true discipleship among many of church-goers. Then they looked back to the life of Jesus and the lives of the martyrs and wondered why there was such a huge disconnect. These radical faithful decided to go back, if not to give their blood like the martyrs, to give their loves in obedience to Christ, denying the pleasures and comforts of the world. These radical ones came to be known as monks and nuns, desert fathers and mothers. Some were hermits, others lived in community, most lived a combination of both.

Why? They saw in the life of Christ and his followers those who had nothing yet possessed the Kingdom of Heaven. Jesus had no wife, no possessions and ‘nowhere to lay his head.’ Jesus lived a life of faithful obedience and prayer—so then should those who follow him. Pelican says, ‘All three virtues vowed by the monk—poverty, chastity, and obedience—were based on Christ as pattern and embodiment.’

He also states, “These monastic athletes, as one scholar has put it, ‘were not only fleeing from the world in every sense of the word, they were fleeing from the worldly church.’ The monasticism of the fourth and fifth centuries was a protest, in the name of the authentic teaching of Jesus, against an almost inevitable byproduct of the Constantinian settlement, the secularization of the church.”

This was a way for those radical disciples of the early church to live out Christ’s life of simplicity. It was also a way of entering into a most blessed and deep communion with Christ himself through prayer.

The Rule of St. Benedictine states‘[do not] value anything more highly than the love of Christ.’

Monasticism touched both the Western part of the church, western Europe in particular, and also the Eastern part of the church, from the Greece to Asia to Northern Africa. From Pachomias to Benedict, Francis and Clare in the West and from Anthony and Mary of Egypt to Basil and Athanasius in the East.

The Monastics experienced a depth in their relationship with Christ and were full of the Holy Spirit—so much so that people would visit monks and nuns for all kinds of healing, and there are records of Monastics levitating in prayer and hearing the direct voice of Christ. What was their secret? It really is simple. Deny yourself and pray—like Jesus did.

How does prayer renew the church? I overheard a conversation at a parish (certainly not mine) where there was a big concern about finances. One person said, ‘boy we really need to commit this to prayer,’ and the other person remarked, ‘we’d better do a whole lot more than that!’

There is a sense in which prayer is a waste of time. There is a sense that there are better things we could be doing with our time. I remember in a seminary course small group I raised the idea of requiring all seminarians to spend time in a monastic setting, to which someone replied, ‘I don’t have time for that, there is too much ministry to do!’

You want to know what is wrong with the church? It is really rather simple. We are not connected to God. Christians of all stripes live there lives as if He did not exist. We are not in his presence. It is plain and simple. The monastics could not help but be in his presence, and on their knees they saved the church from itself.

“Christian experience must necessarily have a mystical, spiritual, non-quantifiable dimension. To be a disciple meaning having the [Trinity] living in us. It means having a supernatural, interior experience that is completely unlike anything available in the world.”

The monk and nun the picture of Christ and his early followers. In lives of holiness and prayer, the world is changed.

In the Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky wrote, through the mouth of the holy elder Father Zosima,

“How surprised men would be if I were to say that from these meek monks, who yearn for solitary prayer, the salvation of Russia will perhaps come once more! For they are in truth made ready in peace and quiet for the day and the hour, the month of the year. Meanwhile, in their solitude, they keep the image of Christ fair and undefiled, in the purity of God’s truth, from the times of the fathers of old, the apostles and martyrs”

Nicely written and cogent post Padre.

What if one is not a monk or nun?

What if all that prayer time and contemplation and obedience to the vow of poverty is interrupted by the hungry cry of a baby?

Interestingly, the Office did not arise from monsticism but from early church practice. I wonder if the hours of prayer (midnight for example) were not the hours of the wee nursing babes in the Christian community. They took the place of the church bells. I’ve no proof of that, of course, but it is a thought.

When I first read your lead question, “What brings renewal to the church?”, my first thought was “service.” Then I read on, and of course, prayer does have to be at the center of what we do, empowering our service. I began attending a parish a couple years ago that has experienced tremendous growth over the past decade, and I think a key component is that they require all participants in the catechism classes to try 3-5 different areas of service. I ended up on the altar guild, and the first time I did the “holy dishwashing,” I really felt like I was a part of the parish, not just someone who attends. Anyway, just a rambling thought from a lurker.

Perhaps an oversimple answer is that as the bride of Christ, the Church needs to do what any couple would do — talk to each other. Isn’t prayer a dialogue? In my personal experience I see people treat their religion like a set of rules and expectations and God like some far off relative they don’t see very often. (I am very frequently guilty of the same.)

P.S. You know, if I could marry Pentecostal fervor in worship with Roman or Orthodox steadiness of adoration, we might have something

Pentecostal fervor combined with the Sacramental life and liturgy, sounds powerful June, where do I sign up?

Jamie,

Lurk away. I like the idea, connection to God inevitably leads to love and service to others. Even the fathers of the desert found themselves minsitering to others in a variety of ways–from mercy ministries (sharing food and shelter with the poor) to spiritual direction.