We often look at the vision of Ezekiel as a shining example of hope, which it is. We must also remember, though that the book of Ezekiel is a dark book.

Ezekiel was prophesying during a time of hopelessness, when Jerusalem and its people were exiled from their homes. Old Testament scholar David Garber says, “We forget that the Babylonians tortured the inhabitants of Jerusalem with siege warfare that lasted almost two years, leading to famine, disease, and despair. We forget how they destroyed the city of Jerusalem, razed the temple to the ground, killed many of its inhabitants, and forced the rest to migrate to Babylon.” Many were enslaved and many died like the vision that Ezekiel saw—piled up in a valley of the shadow of death. Ezekiel’s vision was not a pretty sight but a reflection of a genocide-like slaughter of his own people. Ezekiel himself, a priest, was exiled to Babylon with no Temple to return to, no livelihood and no identity. Even his wife was taken from him.

“Thus says the Lord GOD: Behold, I will profane my sanctuary, the pride of your power, the delight of your eyes, and the yearning of your soul, and your sons and your daughters whom you left behind shall fall by the sword.”

Yet God called him to see disturbing and dramatic things.

The text says that the bones that Ezekiel saw were dry—indicating that they were long dead—a statement of the people of God’s spiritual desolation as well as their physical death. Spiritually desolate because of their idolatry, spiritually desolate because of their disdain for the things of God, spiritually desolate because of their mistreatment of the poor and sojourner.

Often the prophets’ message was to provide theological meaning for the suffering of the people and to provide hope for the future. Ezekiel, in the great prophetic tradition, does both.

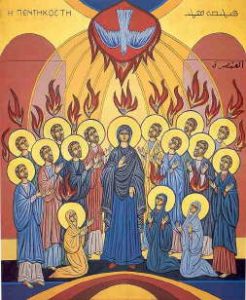

The valley of bones is given sinews and muscle. Then, in an apt Pentecost passage, Ezekiel is commanded to speak to the Holy Spirit himself and ask for the wind, breath, Spirit of God to put life into the bones. God’s own commentary goes like this:

I will make a covenant of peace with them; it shall be an everlasting covenant with them; and I will bless them and multiply them, and will set my sanctuary among them forevermore. My dwelling place shall be with them; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people.

The Day of Pentecost is a partial fulfillment of that prophecy. Ultimately only in the fulfilled Kingdom will this take place permanently, but Pentecost is a foretaste.

In NT Wright’s words, “The future has begun to arrive in the present.”

What is powerful about the Day of Pentecost is that the dwelling of God is not only among the people of God in a place, but through the Holy Spirit there is a dwelling of God in the human heart.

Bishop Wright again:

‘[We] are given the Spirit as a foretaste of what the new world will be like.’ Then he describes the ministry of the Spirit: “The Spirit is the strange, personal presence of the living God himself, leading, guiding, warning, rebuking, grieving over our failings, and celebrating our small steps toward the true inheritance.”